Bruce Clarke was not born in South Africa. His parents who were anti-apartheid activists were forced into exile in London. It was at the School of Fine Arts, University of Leeds, that Bruce Clarke discovered his love for the Arts and Languages in the 1980’s. Following in the path of the fathers of Conceptualism, he began painting against the painting, that is to say that he became involved in decorative painting. This led him to begin merging his love for plastic arts and his need to express his militant discourse.

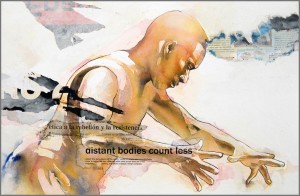

His unique technique gave birth to works of art that reflect a mix of different materials (newspapers, posters, lingual signs, paint splatter, etc.), which rub against, encounter and confront each other. At the same time, they all blend together expressing a new and different meaning. Clarke explains further, ‘‘on the canvas, words and colors, words and images mix up and metamorphose. Each fragment we find or choose has to be decontextualized before they can take up a new meaning- a meaning that may not be the same we beheld at first glance. A transfiguration takes place, a transformation in fact. In a way, I tear down to build-up again.’’

Above all, these elegant graphic compositions are tools for visual and mental deconstruction. They serve to opacify and as well enlighten the mind on contemporary history and on the genealogy of our representations of the African body and its corollary, Africa.

In our present age, where the idea of Contemporary art rhymes with the powers of financial capitalism, the words comitted artist have progressively emptied themselves of all meaning. For Bruce Clarke, the words political artist refer in a way to his work, which involves the exploration of the different forms of domination which were inflicted on and which are still being inflicted on him…on this infamous object: The African body. The African body that was banished and objectified by slavery, battered and beaten by the colonial regime, evicted and starved in the post-colonial era. It remained, all along, a desired body but also, a commodity.

Bruce Clarke has a structural vision of the world that shows the coercive force of the diverse forms of domination and their effects on the actual body and the represented image of the Black man.

Beyond his exploration of the political existence of these oppressed lives, Bruce Clarke communicates a silent message, which is absent but at the same time present. This message reaches out to us through uncompromising gazes, unexpressed rages, submissive but rebellious postures of these characters. Bruce Clarke is certainly one of the greatest stylists of the black body, revealing the intimate battles against the effects of predatory power.

He uncovers the living conditions of the African body and at the same time he constructs some sort of biopolitical message which asks the question: under what material and psychological conditions has the Black Man been able to survive since the dawn of western modernity? His works are a representation of a life that struggles to exist. They are a representation of the wretched of the earth and as Sartre would put it, their tenacity to survive. Brutalized, flogged and oppressed on sugar cane fields, defeated and crushed in numerous resistance movements-where the spear met the gun, starved by bloodthirsty, cannibalistic tyrants who claimed to be brothers, the object of Clarke’s works-The African Body, shows that he rises above very death wish.

With every baneful situation, Clarke’s object- The African Body, shows his will to live.

Bruce Clarke carries on the legacy of his parents in his fight against Apartheid. This shows on the products of his canvas: the lines, shapes, colors, and signs and in his involvment in public action. He was one of the leaders of the project Art against Apartheid held in France. This project sponsored by numerous artists involves a travelling contemporary art exhibition. This will be the starting-point for the future South African post-Apartheid contemporary art museum.

After the democratisation of South Africa, Bruce Clarke became interested in the war in Rwanda especially in the first phases of genocide. After he made a post-genocide photo report, he decided to create a site close to Kigali called The Garden of Memories. A memorial stone sculpture, which was put up in collaboration with the war survivors who came to lay stones in memory of their loved ones.

In fact, Clarke’s different paintings show us their attachment to these bodies and the way they desperately cling to a promise held precious by every human being – a hope for a better life. The becoming of the black body is partly explained in the concept called Upright Men, which was presented at the 20th anniversary ceremony of the Rwandan genocide.

These men, women and children that were victims of the barbarism that stole the last hope that we had in human nature, are now made alive through the paintings of Bruce Clarke. The human is not far from the beast… Beautiful, poetic and political tributes have been given to these human beings (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, up to 1 000 000), who were victims of administrators who decided to separate the Tutsis as the better ethnic group and left the others to think themselves more savage than beasts. This continued till the 100 days of madness when even the Devil feared man.

For Clarke, “these shadows are silent but reincarnate witnesses, which give life to the dead. At the same time, they symbolize the dignity of human life, which was confronted by the mother of all crimes- the denial of the right to life to a whole group of people.

The objective is to publicize this historical event, which has been perceived as an African tragedy. Even so, it serves to remind humanity that in the 20th century, many other genocides took place despite the resolutions and discourse that came after the genocide of the Armenians and the Jews.”

Above this universal memorial for these victims (remembering their names, life paths, smiles and aspirations), Upright men represents all the Rwandans today who have to bear the brunt of this situation, that is, live all together after the war. In more precise words, it involves buying a shirt for someone who slit your mother’s throat after raping her, selling a phone to someone who joyfully butchered a child, riding the bus together, sitting with others in public offices and churches. They have to try to rebuild a life together that was destroyed, because life does not end because horrors begin. In real sense, living together (for all Rwandans- victims or perpetrators), despite all the carcasses around them, is a way of standing tall.

Such artistic work cannot be accomplished alone. It has to be done with other visual artists, Rwandans and Africans, so as to ensure the longevity of the idea of Upright Men. In so doing, it will be in itself a designated memorial, an intimate witness of this unspeakable event, which we must tell of.

Such artistic work cannot be accomplished alone. It has to be done with other visual artists, Rwandans and Africans, so as to ensure the longevity of the idea of Upright Men. In so doing, it will be in itself a designated memorial, an intimate witness of this unspeakable event, which we must tell of.

The works of Bruce Clarke are an autopsy of the black body, who has been a receptor of the most extreme acts of domination (as a lab rat which has been tested to the extreme). Put side by side, these canvases unfold the long African history and open up a dark dialogue on these memories. These reincarnated beings are a constant reminder of the man-made malediction that hit the continent.

Drowned in the darkness of enlightenment, the Black Man was taught to “tighten his belt, like a valiant man” [1], without ever tasting the fruit.

Bruce Clarke certainly shows the tragedy of the Black Man, but he also exposes the indomitable strength of one, who every day, courts the idea of death as an intrusive neighbor. In reality, no previous series of this artist has ever exposed such cruel optimism and as well, celebrated the idea of life with macabre signs.

[1] Notebook of a Return to Native Land/ Aimé Césaire. – Paris: Présence africaine, 1956

Tabué Nguma

Translated by : Onyinyechi Ananaba

Bruce Clarke Website: http://www.bruce-clarke.com/

The project Upright men: http://www.uprightmen.org/

Bruce Clarke n’est pas né en Afrique du Sud. Activistes anti-apartheid, ses parents ont été contraints de s’exiler à Londres. Et c’est aux Beaux-Arts de l’Université de Leeds, dans les années quatre-vingt, qu’il est initié au mouvement Art et Langage. S’inscrivant dans la continuité des pionniers de l’art conceptuel, il s’attachera rapidement à peindre contre la peinture, entendons la peinture décorative, avant de tendre vers une recherche conciliant expérience esthétique plastique et discours militant.

Bruce Clarke n’est pas né en Afrique du Sud. Activistes anti-apartheid, ses parents ont été contraints de s’exiler à Londres. Et c’est aux Beaux-Arts de l’Université de Leeds, dans les années quatre-vingt, qu’il est initié au mouvement Art et Langage. S’inscrivant dans la continuité des pionniers de l’art conceptuel, il s’attachera rapidement à peindre contre la peinture, entendons la peinture décorative, avant de tendre vers une recherche conciliant expérience esthétique plastique et discours militant.