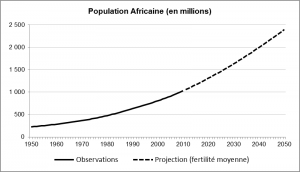

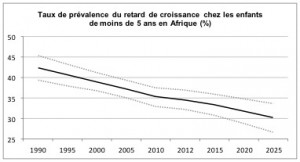

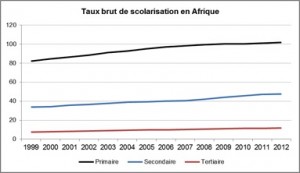

In Africa, 60% of the unemployed are under the age of 25[1]. Both policy makers and the youth themselves have embraced entrepreneurship as the panacea against youth unemployment. As a matter of fact, governments all over the continent have implemented numerous projects to support this growing interest of the youths to start their own company. 25% of the projects are geared towards young people[2] and 35% of unemployed people seriously think about becoming entrepreneurs[3]. Is this growing interest in entrepreneurship actually becoming a reality? Could Africa be an exception to this reality? Are there any alternative options for youth employment in Africa?

The truth about entrepreneurship outside Africa

The lack of financial support is definitely one of the major constraints for entrepreneurs in the continent. If we have a look at the situation in other countries where access to funds and bureaucracy are more favourable to entrepreneurs, we see that new businesses have a high failure rate. For instance, in the USA, the past two decades have seen the development of some of the most successful companies (Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple). However, statistically, new startups only have a 50% chance of becoming successful.

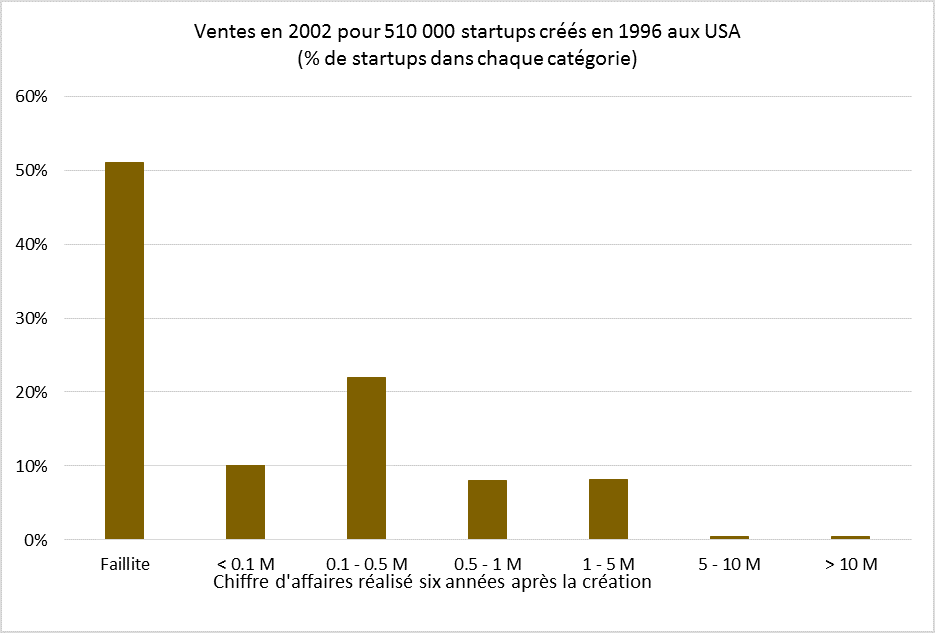

In the figure below, we can see that only 50% of startups have made a profit 6 years after their set up. The successful businesses do not always generate a very high turnover. Less than 1% of businesses have generated more than 5 million dollars in 6 years of existence. Having a successful business can be compared to a lottery. There are very few winners and it is all a question of luck. Even in a country where there are no major obstacles to entrepreneurship, only 1% of businesses will get the chance to expand and become a large company.

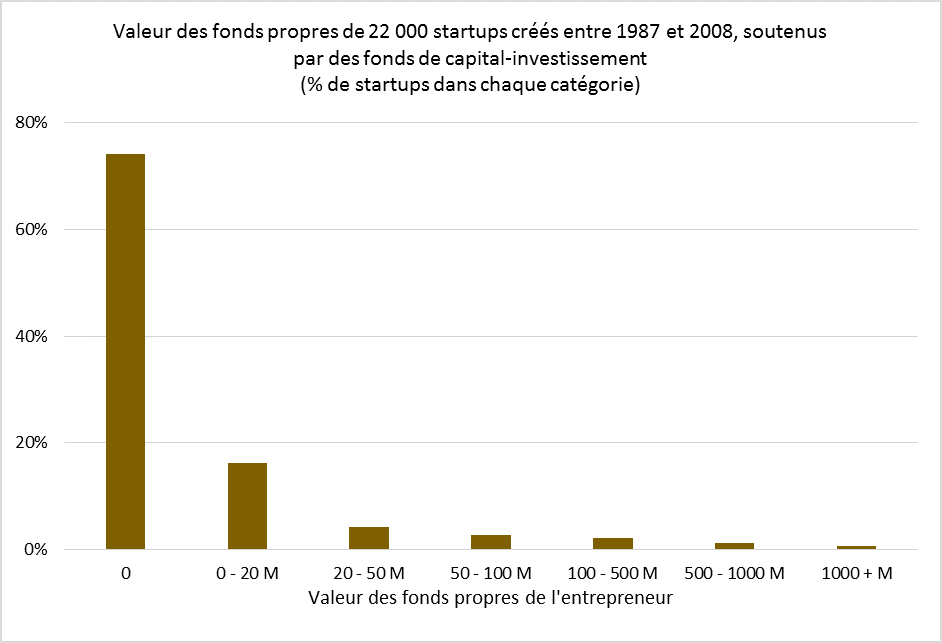

Some might say that it is too early to assess the success of a company after only 6 years. It is actually not true. In a survey covering over 22 000 businesses in the USA from 1987 to 2008, it is clear that 75% of companies do not have any stock-market value many years after their creation. Again, less than 1% of the businesses reach a stock-market value of more than 500 million US dollars. Whether we wait 6 years or more, it is a reality that barely 1% of small businesses become large companies. Our perception of entrepreneurship is altered by the way it is presented to the public. We only see the success stories and don’t know about the vast majority of businesses that don’t make it, just like in a lottery.

Playing the lottery of entrepreneurship is not a bad thing. The problem is that hundreds of job seeking people are under the illusion that their future lies in entrepreneurship. Moreover, as far as income is concerned, an employee is on average wealthier than an entrepreneur [4]. Multimillionaire entrepreneurs do exist but they are much rarer. As an employee, you are guaranteed to have a higher income than the average entrepreneur. How can we make entrepreneurship a solution for youth unemployment in Africa?

Is Africa an exception ?

In Africa, the extensive margin of entrepreneurship (traditional economic activities) is actually as significant as the intensive margin (innovations) because the middle class is growing progessively and consumes more goods and services. In industrialised countries, the technologies to produce these goods and services have already been developed in the food and agriculture, IT, transportation, financial sectors. Hence, it is very difficult for a local entrepreneur to succeed in these developing industries without any state protectionism.

As a consequence, in most African economies, the supermarkets are not the results of the merger of local shops. The market is dominated by multinational companies. It is the same situation in the fields of transportation, energy and digital technology. Multinational companies that invest in traditional sectors do contribute to create employment. However, all the jobs that were lost cannot be replaced because these companies have very efficient production technologies that require less labour force for the same production levels.

As a matter of fact, young entrepreneurs do not invest in these traditional sectors. They prefer investing in the intensive margin, especially in projects involving digital technology and renewable energies. This margin is the focus of the studies presented above on business performance in developed countries. It is by definition very uncertain because it is based on innovation. There is a high failure rate in this field, especially in the United States because there is not much opportunity for digital services and access to energy. Before the emergence of Facebook, many similar social networking sites and other innovative services tried their luck but were not successful.

In Africa, we do not have enough hindsight to assess the impact of the business incubators for entrepreneurs who try their luck in this lottery. Africa does not offer better opportunities for success in business than other developed countries. It is quite the opposite. African entrepreneurs are limited in their endeavours by difficulties in accessing finance and by the bureaucracy. What are the solutions for youth employment in Africa ?

A sketch of the alternative solutions to tackle youth unemployment in Africa

There is no miracle solution. However, African states can implement systems that worked in other developed countries such as France or the United States. In France, most major industrial groups (Renault, Peugeot, Airbus, SNCF, etc) employ thousands of people and work with many sub-contractors. The construction of a single ship is enough to guarantee employment to thousands of people for a decade. Four contracts will guarantee life employment for thousands of people. Industrialisation is one of the first solutions for youth employment.

It is a given that industrialisation is the way to go for Africa. But how should it be developed ? We suggest that industrialisation should be integrated into the new global value chains.[5] These global value chains have still got to be identified and integrated. This solution is not ideal because it is difficult to coordinate the activities of local agents and agents that are outside of the continent. This is why the integration in the global value chains is not declared. In fact, it accomplishes itself in the framework of an economy that entails comparative advantages in the production of certain intermediate goods and services. This is not the case in most African countries. As a matter of fact, a report from the Center of Global Development states that the labour cost is higher in Africa than in other comparable economies.[6]

The solutions for employment in Africa lies in the development of a local market creating competition between local industries. This strategy consists in awarding public contracts to local companies after an effective competitive procedure. With this procedure, the companies are encouraged to get the latest technologies in order to be more competitive. This procedure is very common in the United States, China, and in Europe to a certain extent. Another solution consists in merging companies in the informal sector in exchange for subsidised access to private funding. This is a good solution to protect young unemployed people in Africa from the wave of multinational companies that is spreading across the continent. These companies are attracted by an emerging middle class and seek new sources of growth. These solutions will not solve the issue of unemployment of millions of young African people. However, they will contribute to fight against a situation threatening social peace in African nations.

Translated by Bushra Kadir

[1] 2009 data by the BIT, as referenced in the 2012 African economic prospects http://www.africaneconomicoutlook.org/fr/thematique/youth_employment/

[2] Results of a survey by experts in the 2012 economic prospects in Africa.

[3] Data of Gallup World Poll (2010).

[4] Data from the Bureau of Statistics in Denmark .

[5] The report on 2014 economic prospects in Africa already mentionned this solution for Africa's industrialisation.

[6] Gelb et al. 2013. « Does poor means cheap ? A comparative look at Africa’s industrial labor costs » Working Paper N° 325, Center of Global Development