Depuis le dimanche 1er septembre, le pays est en proie à de violentes manifestations xénophobes. Ces évènements malheureux ont déjà fait plus de 10 morts. Les motifs de ce mécontentement sont pour le moins vagues : les étrangers sont pointés du doigt comme étant des « voleurs » de travail. [1]

C’est la troisième fois que le pays connaît des troubles à caractère xénophobe après ceux de 2008 et 2015.

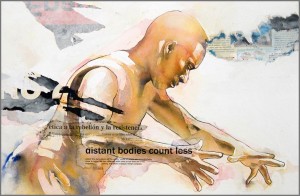

Si la situation actuelle nous incite à faire le rapprochement avec les tensions raciales d’alors, causées par l’instauration d’un régime d’apartheid, elle présente tout de même des caractéristiques sociologiques hautement symboliques : des populations noires, en colère, qui s’attaquent à l’intégrité et aux intérêts de populations étrangères, pour la plupart venues d’Afrique subsaharienne ou du moyen orient.

Une très forte inégalité sociale

Ce contraste traduit une réalité sociale historique et politique mouvementée. En dépit du dynamisme économique et de nombreuses ressources minières qui font de l’Afrique du Sud la première puissance économique d’Afrique Australe[2], la situation sociale demeure mitigée. Le pays présente un taux de chômage de près de 27% et l’insécurité devient de plus en plus grandissante. L’écart social entre les communautés blanches et noires est alarmant : le revenu des familles blanches reste 5 fois supérieur à celui des familles noires soit 35 739$ par an pour 7479 $ par an pour les noirs. 75% des fermes appartiennent toujours aux Blancs et 1 noir sur 20 décroche un diplôme d’études supérieures. 20% des foyers noirs vivent dans une extrême pauvreté contre seulement 2,9% des blancs. 47 % des sud-africains Noirs seraient concernés par le taux chômage contre 11,7% des blancs.[3]

Cette inégalité sociale est malheureusement l’un des héritages obscurs de la période post apartheid, et les événements actuels témoignent d’une exaspération, tout de même maladroite d’une communauté sans repère et obligée de s’en prendre aux populations étrangères, considérées à tort comme la cause de tous leurs malheurs.

Pourtant, l’explication à donner à cette soudaine poussée de violence nous amène à questionner l’histoire politique Sud-Africaine et revenir à la période de lutte contre l’apartheid.

La période d’Apartheid, germe des difficultés d’aujourd’hui

Ce retour en arrière peut se scinder en deux périodes : la période des négociations pour la fin de l’apartheid, et la période post apartheid avec l’accession de l’ANC au pouvoir en 1994

La première période (1989-1990) que l’on qualifierait de période de négociation, fut caractérisée par une série de réformes politiques (autorisation des parties politiques interdits, libération de prisonniers politiques dont Nelson Mandela en vue d’aboutir à la fin du régime d’apartheid). Ces réformes ont été conduites par Frederik De KLERK, qui a succédé à P. W Botha, symbole du régime d’apartheid.

La seconde période (1990-1994) est celle qui, selon, nous aura atténué la lueur d’espoir portée en Nelson Mandela et ses compagnons. Cette période marque la réussite des négociations et débouche sur l’élection de Nelson Mandela en tant que premier président noir d’Afrique du Sud. Mais ces négociations vont cacher malheureusement des compromis qui s’avèreront lourds de conséquences. L’un des gestes forts de la période post apartheid est la formation d’un gouvernement d’union nationale. Ce gouvernement était constitué de toutes les forces politiques du pays dont L’ANC et l’ex parti au pouvoir, le National party. Derrière ce symbole d’unité nationale retrouvée et de réconciliation, se cache la sauvegarde de plusieurs intérêts économiques de la communauté blanche.

L’abrogation de certaines lois racistes (le land act qui réservait 87% du territoire aux blancs, le population registration act, pilier législatif de l’Apartheid) n’a pas été suivie d’actes concrets.[4]

Sur le plan économique, un fait majeur illustrera notre position. En juin 1996, le gouvernement va opérer un basculement avec la substitution du programme initial de l’ANC, le programme de reconstruction et de développement (le RDP), au profit d’un nouveau document programmatique présentant la nouvelle stratégie macro-économique adoptée par le gouvernement sud-africain. Ce texte sur la croissance, l’emploi et la redistribution marque l’abandon des options de développement et d’industrialisation se fondant sur la croissance de la demande intérieure au profit d’une perspective ouvertement néo-libérale, conforme aux stratégies de la Banque mondiale : dans ce nouveau cadre, l’objectif prioritaire de la croissance repose sur la bonne volonté des investisseurs qui doit être encouragée par la limitation des déficits publics, la baisse de la fiscalité pesant sur les entreprises, la limitation des hausses de salaire, la flexibilité du marché de l’emploi et l’accélération des privatisations. Cette nouvelle orientation stratégique a eu inévitablement des effets négatifs sur l’emploi et n’a fait qu’aggraver l’inégalité raciale existante que le nouveau gouvernement avait du mal à éradiquer.[5]

En définitive, cette cohabitation a eu pour effet de transformer les enjeux initiaux portés par l’ANC. La vision de transformation complète de la société sud-africaine a cédé le pas à un ordre économique et social qui n’a été vidé de discrimination raciale que sur le plan institutionnel. Cette cogestion politique ainsi que la transformation des objectifs économiques n’ont fait que creuser le fossé existant entre les communautés. Les nombreux scandales de corruption qui gangrènent le paysage politique sud-africain actuel et la flambée du taux de criminalité sont sans surprise les fruits d’une période de marchandage politique permanent marquée par des concessions naïvement acceptées.

C’est donc un peuple sans repère qui s’en prend injustement aux investisseurs jadis accueillis à bras ouverts, sous le regard impuissant d’un gouvernement déjà débordé par des crises internes.

Loin de nous l’idée de remettre en cause les longues années de lutte acharnée pour la liberté, laquelle fut acquise parfois au prix du sang et de privations. Bien au contraire, le gouvernement Sud-africain devrait tâcher à engager de véritables réformes pour pallier ces inégalités aux conséquences désastreuses, et achever de la plus belle des manières le combat mené par le vieux Madiba.

Désiré Gnoto

[1] https://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2019/09/04/l-afrique-du-sud-en-proie-a-une-vague-de-violences_5506218_3212.html

[2] Source : Direction générale du trésor

[3] https://www.agenceecofin.com/hebdop3/0905-65984-revenus-education-foncier-tour-d-horizon-des-inegalites-entre-noirs-et-blancs-en-afrique-du-sud-25-ans-apres-l-apartheid

[4] https://www.jeuneafrique.com/66950/archives-thematique/fin-de-l-apartheid/

[5] Pour une analyse complète : Copans Jean, Meunier Roger, Introduction : les ambiguïtés de l’ère Mandela. In: Tiers-Monde, tome 40, n°159, 1999. Afrique du Sud : les débats de la transition. pp. 489-498