"When the missionaries came to Africa, they had the Bible and we had the land. They said 'Let us pray.' We closed our eyes. When we opened them we had the Bible and they had the land." Desmond Tutu

"When the missionaries came to Africa, they had the Bible and we had the land. They said 'Let us pray.' We closed our eyes. When we opened them we had the Bible and they had the land." Desmond Tutu

Land in South Africa is both a controversial and an important topic. It is controversial because the Native Land Act set in 1913 excluded the vast majority of native South Africans from owning land while favoring the Afrikaners (white settlers). As a matter of fact, only 7% of the agricultural land was set aside for the black population, though they comprised nearly 70% of the population at that time[i]. An important topic it is as the unemployment rate in South Africa is high and is even greater in rural areas. Therefore, restructuring the land could lead to potential social and economic gains.

When Apartheid was brought to an end, a new government was elected and with it the hopes of change for most South Africans. Thus, it is crucial to examine if there has been a significant change in the distribution of land in South Africa since then.

The initiative of the Government

In 1994, at the end of apartheid, almost 90 percent of the land in South Africa was owned by white South Africans, who make up less than 10 percent of the population[ii]. The newly elected government promised that it will redistribute one third of the land to the black population. It developed two fundamental actions in order to resolve the problem: redistribution and restitution of the land.

At first, the government focused on the redistributing the land. It consists of buying the land from the owners that benefited from the Native Land Act and then restore it to the population that was evicted. This action is also known as the “willing buyer, willing seller” method : in order for the government to obtain the land it has to be bought on the market first. And for the land to be found at the market, it has to be sold by the current owners. Of course, the owners are not forced to sell their land.

But, restitution is another important action undertaken by the South African government and is complementary to distribution. Indeed, this practice consists of donating to the population that has been harmed by the Native Land Act a cash payment rather than the land itself. It is quite a popular deal for poor residents in urban areas that have no desire to return to the rural areas. However, as with any policies, there are limitations to what has been achieved so far…

Limited Actions

The government promised that it would redistribute one third of the land; however; 20 years later less than 10% of the land has been given back.[iii] How can this failure be explained?

Initially, redistributing the land is not enough. Education during Apartheid proved to be insufficient and as a result new owners lack the necessary knowledge and skills required to operate the acquired land. In addition to this, operating a farm also proves to be quite expensive; therefore new owners that suffer from financial constraints do not have the sufficient means to accomplish their work. Such problems need to be addressed in order for South Africa to progress.

Progress and Prospects

Supporting new farmers is an important step that should be taken by the South African government. Subsidies (money support) could be granted to them. Not only does it facilitate the selling of their agricultural products, it also allows them to buy machinery and equipment that facilitate their work by making it more productive. On a larger scale, more ambitious projects should be proposed by the South African government. Such projects include education and government spending that help future farmers and narrow the gap that was created during Apartheid. South Africa can learn from its neighbours that suffer with the same problem.

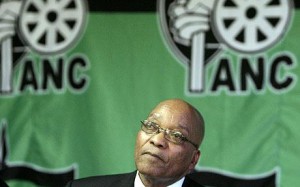

On the one hand, there is Zimbabwe with its radical measures such as seizing the land and redistributing it in an arbitrary manner. This method has many implications. At first, it is important to admit that even though South Africa and Zimbabwe share the same problem, they choose to deal with it differently. Mandela’s ANC (African National Congress) fought for racial equality, when it saw that land distribution represented a topic of hatred and potential payback for native South Africans, it was not seen as an urgent objective even though it remained important in the agenda of the government. For instance, when examining at the budget granted to land reform (1% of the South African budget as of 2013)[iv], we can observe that this issue is dealt with caution. Also, confiscating the land (without compensation for the owner) is forbidden by the South African Constitution. In the case of an (unlikely) constitutional reform, such land seizing can harm the South African stability, and can have negative long term consequences.

On the other hand, there is Namibia and its more subtle approach. In Namibia, land has to be bought individually either with the buyer’s own money, or by making a loan facilitated by the Namibian government. This method proves to much more successful as a quarter of the land has been redistributed since the country’s independence in 1990. Surely, South Africa can benefit from the Namibian experience as so far only 8% of the land has been redistributed.[v]

In conclusion, we can assert that the South African government presents noble intentions regarding the reform of land, especially when we examine the procedures made available. However, such methods have proven to be limited. As a solution, the agricultural market should be regulated while supporting new farmers. It is unlikely that in the future extreme solutions such as seizing the land would be proposed as it is illegal and represents too much of a danger for the rainbow nation. Perhaps a change in the methods employed can be expected in the future as President Jacob Zuma recently declared that: “foreigners will soon be banned from acquiring South African land”.