How is the digital tide taking care of the digital divide? At the start of the new millennium, there was global concern that poor countries, especially in Africa, would be twice left out: economically and also technologically. Fortunately, the digital divide never became a global challenge. In fact, it is closing faster than anyone had imagined. In some parts of the developing world there are even budding signs of possible digital overtaking.

How is the digital tide taking care of the digital divide? At the start of the new millennium, there was global concern that poor countries, especially in Africa, would be twice left out: economically and also technologically. Fortunately, the digital divide never became a global challenge. In fact, it is closing faster than anyone had imagined. In some parts of the developing world there are even budding signs of possible digital overtaking.

Kenya is one of few African countries driving in the fast lane. Over the past decade, it has experienced a sweeping “digital tide”. Today, Kenya has crossed the 30 million threshold of active cell phone numbers, up 29,000 from 12 years ago! Almost everyone can now afford to buy a phone, which sell for as little as Ksh 500 (or US$5) on the flourishing second hand market.break People are also spending more on communication. in 2012, Kenyans have spent on average US$65 on communication, compared to US$45 a year ago.

Moreover, Kenya, East Africa’s powerhouse, has reached two other milestones in 2012 : 20 million users of mobile money and 15 million internet users, thanks largely to ubiquitous smart phones (see figure).

Now that everyone can own a phone, even in poor countries, is the mobile revolution over? Has everything that can be invented actually been invented – a claim famously associated with a commissioner of the US patent office in the 19th century?

We actually think the opposite is true: a new wave of innovation is starting, which will exploit increased connectivity to bring new solutions to old problems, including in development policy and economics. Here are three early examples of such innovation:

First is public sector accountability. In Kenya, a new service called “I Paid A Bribe” lets people expose bribery cases by reporting them online or by SMS. In less than one year, the site has reported corruption cases ‘worth’ over half a million dollars (mainly to traffic police and other government officials).“I Paid a Bribe” has helped to expose the problem publicly, which is the first step to tackling it. Similar services could also help monitor other areas of government performance such as quality of health services, teacher attendance and power services. The Kenyan government’s pioneering resolve to open-up public data at Opendata.go.ke is a good first step in making government and public services more accountable more broadly. The database is a gold-mine for developers and civil society that have already developed great uses.

Second is economic and social welfare monitoring. Previously, socio-economic data was tediously collected via paper surveys. The results were typically available to policy makers and researchers two-to-three years later when, frankly, they were often no longer relevant. In South Sudan, the National Bureau of Statistics and the World Bank have leveraged the expansion in mobile coverage to monitor how economic and social conditions are changing in near-real-time in the young nation. Last year, they conducted a monthly phone survey, with a sample of households, asking questions about their economic situation, security, outlook, and other topics.

This year, they used cellphone-enabled tablets to collect data on food security and market prices. Such high frequency, real-time data has never been available before. It is already revolutionizing how policy makers can identify problems and bring timely solutions. As Marcelo Giugale of the World Bank puts it: High-frequency data has the potential to do “to economics what genetics did to medicine”.

Third, the explosion in mobile phone and internet leaves behind ‘digital traces’ of human behavior which can help to better understand development challenges. For example, recent research by Harvard scientists using Kenya data, published in Science last month, shows how mobile phone data (tracking people’s movements) can be used to trace the spread of malaria. By conducting such monitoring in real-time, officials could for example send text message warnings to people traveling in high-risk areas and pre-position testing equipment and drugs.

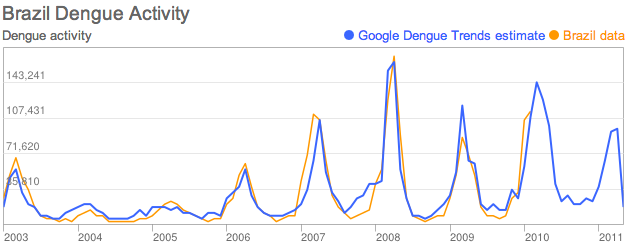

There are many other examples of such use of ‘big data’ for economic, social and policy purposes. Google has demonstrated how search data can predict dengue breakouts in Brazil, India and Indonesia by monitoring how people search for dengue-related topics and symptoms. In Indonesia, the UN Global Pulse and a research firm used Twitter data to monitor food prices with surprising accuracy, finding that the way people spoke about rice on Twitter could be correlated with the actual market price of rice. As internet use increase in Africa, large amounts of digital traces will be available and useful for monitoring and tackling social problems also here.

These examples are just the tip of the iceberg, with many more applications of new technology to be discovered. Traditionally, data was used and analyzed by “experts” within government and research institutions. Today, with more available (open) data, better visualization tools, and new, socially concerned IT developer communities, the universe of users is expanding fast. Groups of expert and volunteer computer programmers are making data accessible to the public, popularizing its use and finding technical solutions to real-world issues.

The digital divide is behind us. This generation’s challenge is to leverage the new “digital tide” for the public good. Some early innovations are already very promising and there will be many more to come.

An article by Wolfgang Fengler, lead economist in trade and competitiveness (World Bank)