As a young Moroccan woman who aspires to participate in the management of public affairs in my own country, I often wondered: what would prevent me from becoming a corrupt political leader? What pre-disposes so many transparent young individuals to become corruptible decision-makers? How to ensure that citizens will not abuse entrusted power for private gain? I could not obtain a complete and satisfying answer to these questions. However, my engagement in a consultancy project with Transparency International[1] gave me some elements of answer. It is particularly during my visit to Niger that I got the most insightful perspective. Indeed, I got the chance to interview Mrs. Salifou Fatimata Bazèye; one of the most powerful women in the country. In addition to her achievements as the president of the Constitutional Court, her integrity made her an icon for the promotion of rule of law. When I asked her: What made you resist to corruption? She answered: My values.

Indeed, the fight against corruption is a multidimensional process. If institutional capacity and political will are indispensable to prevent and combat corruption, we often tend to underestimate the role of culture and values. In this post, I have decided to bypass -indispensable- institution-building mechanisms and anti- corruption policies, and rather shed light on system of values as both an asset and a tool in the fight against corruption. Therefore, I will share some of the best practices adopted by Transparency International (TI) and its Nigerien chapter, the Nigerian Association for the Fight against Corruption (ANLC), in its effort to highlight transparency and merit within the existing system of values.

The ALNC: the Transparency International chapter in Niger

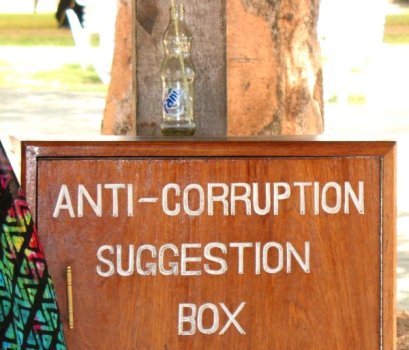

The ANLC plays a key role in the Nigerian civil society. It is the driving force behind national efforts to fight corruption, which is endemic in the country. Ever since its creation in 2001, the ANLC promotes reforms in favor of transparency in public and private management as well as transparency in national and international transactions. However, one of the most important dimensions of the ALNC is its activities that directly engage citizens to report and fight fraud.

In 2010, the Advocacy and Legal Advice Center within the ALNC was established with the rationale that the fight against corruption would be more effective if ordinary citizens were engaged in reporting. In that sense, the association has conducted panoply of activities including meeting and exchanges; public awareness campaigns; conferences in universities; workshops and trainings targeting youth, women, judges and elected officials; as well as the publication of studies and reports.

The fight against corruption requires both institutional and behavioral change

Hence, the ANLC attempts to tackle corruption at all scales; thereby addressing petty, grand, and systemic corruptions.

At the macro-level, it plays a key role in supporting national efforts to renegotiate exploitation contracts with foreign companies. It initiated petitions and campaigns. It also spearheads inspection missions in major industries. Even Nigerien citizens are well aware that corruption is intrinsically structural and mainly linked to systemic causes. The majority of locals I interviewed emphasized that the heart of corruption lies in the extractive industry. Referring to the big gap between Niger's natural endowment (uranium, oil, gold, vast land) and its poor human development (ranked at the bottom of the Human Development Index[2]), most Nigeriens are aware that the terms of exploitation by foreign companies and the complicit acceptance of a corrupt political elite are the root causes that shape corruption in the country.

Nonetheless, the ANLC rejects “the wait and see attitude”, and undertakes measures that promote both institutional and behavioral change. It calls for citizens to promote change, but also to embody the values of integrity that they foresee for their country. The association deploys considerable effort to involve citizens. It aims to activate a system of values that encourages the people to control, condemn, and reject corrupt acts in all aspects of life.

Five best practices in engaging citizens

In that sense, the ALNC adopts five key principles:

1- Autonomy

The ALAC embraces the principle of “autonomization”. Its role is to inform, assist, and build citizens’ capacity to counter corruption. It does not aim to create a relation of dependency and refuses to substitute for the individuals. It rather provides citizens with juridical tools, instruments, and guidance. That includes Direct Juridical Assistance through a hot line “7777” (to foster anonymity) and through in-person complaint reception.

In addition, it mobilizes traditional and modern media such as public speak-outs, radio and television commercials to reach out to the public. It also relies on music, theater, and arts to appeal to youth and promote transparent behavior among them.

2- Inclusiveness

Furthermore, the ALNC staff organizes regular awareness campaigns in rural areas. I had the chance to participate in six field missions in rural communes, and I personally think that these are the most intense and powerful activities for the organization. In fact, these visits are impactful because they are both participatory and inclusive.

First, the ANLC integrates traditional actors and capitalizes on their educational influence. For instance, religious and traditional leaders are integrated as partners. On the one hand, chiefs of villages often play a key role in mobilizing the locals and maximizing their attendance. On the other hand, religious leaders use religious references (such as Hadiths, Quran, and Sunna) to support the ALNC’s promotion of honesty, transparency, and justice; and do even encourage citizens to report, reject, and condemn corrupt acts; as part of religious practices.

Moreover, sensitization campaigns particularly target women’s groups and youth. The ALAC's outreach strategies have been effective thanks to its gender and social considerations. Indeed, women are included –and often the major targets- of the campaign. Not only do women tend to be well organized in these structures, but they also have a spillover effect. Women’s educational role within families is leveraged by the organization; thereby aiming to capitalize on their role of “moral teachers”.

Second, awareness campaigns are not organized in a unilateral and one-way conversation. On the contrary, the locals are engaged in interactive discussions. They are invited to define corruption, give examples, share their experiences, identify causes and find potential solutions. There personal testimonies and analyses are eye opening for participants. They are encouraged to think of corruption and directly identify with concrete examples.

3- Responsibility

TI staff encourages consciousness of the role and responsibility of the citizens. Breaking away from the discourse of passive victims, the facilitators directly point to the harmful practices of citizens: “You want the state to deliver, but what do you do for the state?” (TI facilitator, during sensitization campaign). They stress that petty corruption benefits to individuals and impoverishes the state; which consequently is less able to deliver for the citizens.

Hence, Nigeriens—women and men—are called to understand themselves as real citizens; thereby, comply with the law and respect their obligations. As an example, the ANLC facilitators highlight how the act of selling one's votes during political elections frees political leaders from any accountability. Thus, they call for a commitment of citizens at the grass-root. The power of change is put within the citizens.

4- Role Modeling

The facilitators also give positive examples of people who denounce and fight corruption. These successful cases are emphasized in order to fight defeatism and reject counter-models of people who succeed through dishonest means. For instance, the case of Mrs. Salifou Fatimata, ex-president of the constitutional court, who resisted to corruption and intimidation, is raised as a success story: “At the beginning of her career, a man attempted to corrupt her. She sent him to jail. After that no one approached her and attempted to corrupt her. So, it is possible! “(Mr. Nouhou, secretary of TI in Niger). The ALNC asserts the need to celebrate the right examples.

5- Delegation

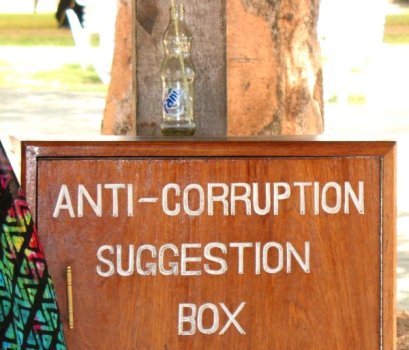

Last but not least, the ALNC ends every sensitization campaign with the creation of local anti-corruption clubs. These are community-based entities and local branches of the ALNC that ensures the durability of the sensitization campaign.

The boards of the anti-corruption clubs are elected by the local participants the day of the sensitization campaign. Later, they are trained to inform and assist locals in their reporting and fight against corruption. Interestingly, women do often dominate in terms of seats, which might challenge many assumptions with regard to Niger and other countries in the region.

Conclusion

To conclude, this short post does not aim to undermine the crucial importance of policies and institutional anti-corruption mechanisms. It rather aims to voice a local perspective on the question. Indeed, I consider that the leaders and locals I interviewed are pointing to a direction we should not neglect. What they refer to as “a crisis of values” is a deep factor in the spread of corruption. Thus the fight against corruption cannot be won through laws alone, it requires us to raise awareness and re-activate positive norms within society.

Lamia Bazir

[1] I was one of the six students from the School of International and Public Affairs (Columbia University) who were selected to work on a project on Gender and Corruption. The consultancy lasted for a period of seven months (Nov. 2013 to May 2014). It involved field visits in Niger and Zimbabwe.

[2] Niger was the country with the lowest Human Development Index in the world in 2014 (0,337)

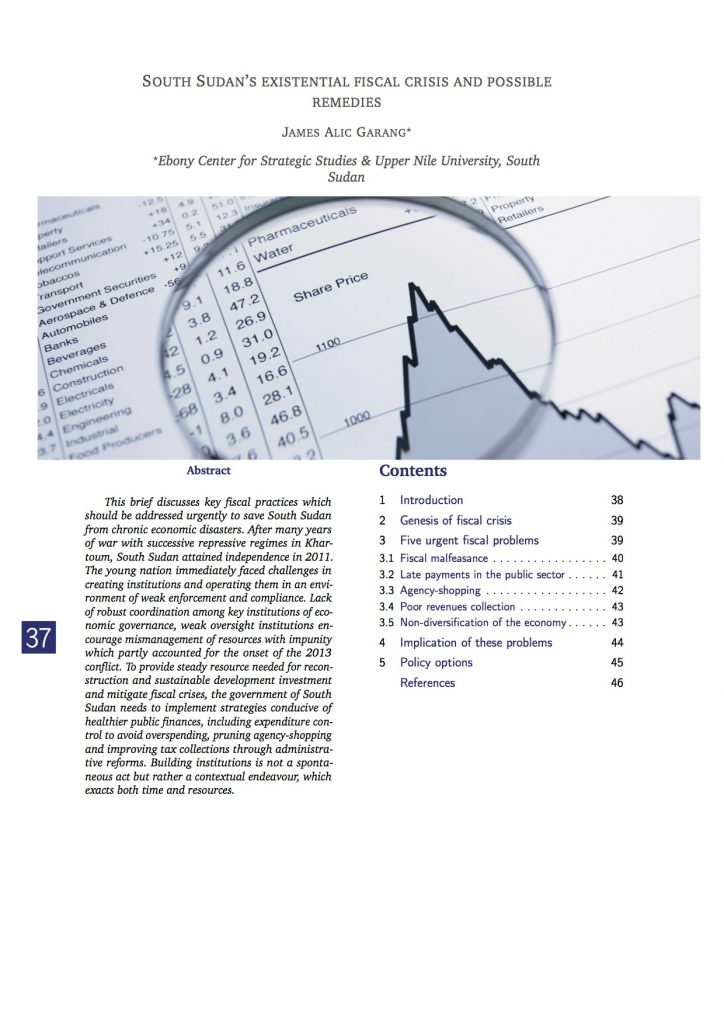

This brief discusses key fiscal practices which should be addressed urgently to save South Sudan from chronic economic disasters. After many years of war with successive repressive regimes in Khartoum, South Sudan attained independence in 2011. The young nation immediately faced challenges in creating institutions and operating them in an environment of weak enforcement and compliance.

This brief discusses key fiscal practices which should be addressed urgently to save South Sudan from chronic economic disasters. After many years of war with successive repressive regimes in Khartoum, South Sudan attained independence in 2011. The young nation immediately faced challenges in creating institutions and operating them in an environment of weak enforcement and compliance.

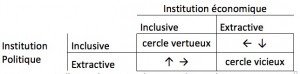

Le développement ne serait-il qu’une question de financement ? On est bien tenté de répondre par l’affirmative en partant du modèle proposé par Arthur Lewis (1960). Sous une perspective historique, on s’aperçoit cependant que les nations les plus prospères (e.g. Egypte antique, Rome) n’ont pas réussi à conserver leur prospérité à travers les siècles. Plus récemment, lorsqu’on observe qu’une nation aussi prospère que la Lybie soit bombardée et réduit à un champ de batailles entre milices, la question de la suffisance des moyens financiers pour le développement reste entièrement posée. Si les moyens financiers sont nécessaires au processus de développement, les observations précédentes illustrent à quel point ils ne suffisent pas pour garantir l’élévation permanente du bien-être de la société. Suivant les travaux récents de

Le développement ne serait-il qu’une question de financement ? On est bien tenté de répondre par l’affirmative en partant du modèle proposé par Arthur Lewis (1960). Sous une perspective historique, on s’aperçoit cependant que les nations les plus prospères (e.g. Egypte antique, Rome) n’ont pas réussi à conserver leur prospérité à travers les siècles. Plus récemment, lorsqu’on observe qu’une nation aussi prospère que la Lybie soit bombardée et réduit à un champ de batailles entre milices, la question de la suffisance des moyens financiers pour le développement reste entièrement posée. Si les moyens financiers sont nécessaires au processus de développement, les observations précédentes illustrent à quel point ils ne suffisent pas pour garantir l’élévation permanente du bien-être de la société. Suivant les travaux récents de