ADI: How does Google aid the development of the Digital ecosystem in Africa? And why does Google do it?

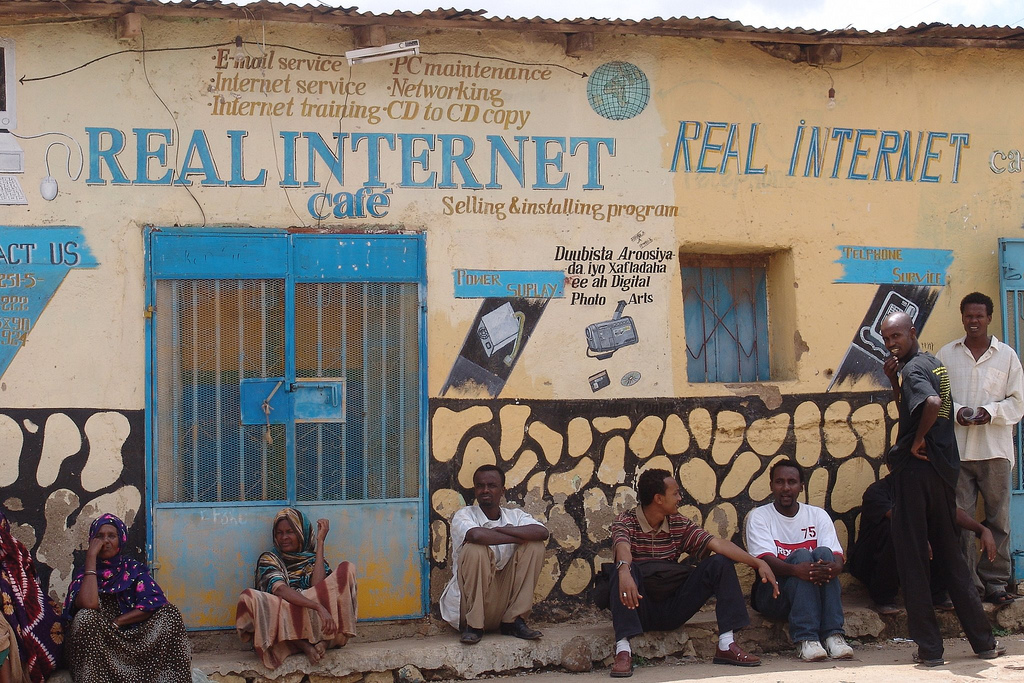

We do so because we are convinced that the region needs an internet ecosystem that is dynamic and as well open. That is to say, an internet system, where each person has free access to information that he needs without any hindrance. Despite the developments that we see in mobile internet, it is still insufficient. We have not yet reached the cut-off mark. The speed and penetration rate are still low. For example, one cannot play a high definition video without the question of data coming up or the short waits to allow the videos to buffer. We can’t still do a lot on the internet and it is quite expensive. Even those who go on the internet still do not have access to high-speed internet (broadband).

However, there is a new trend of providing limited internet access to well-known sites. In fact some Internet service providers (ISP) offer packages that only give access to these selected sites. However, if an entrepreneur starts to provide a new service, his service is not included in this package and is therefore not accessible to all. This forms the base for our need to have an internet platform that is open to all. We are presently trying to tackle three aspects:

We are working on problems of access to internet. That is the infrastructure that limits access; price and regulatory problems that limit the development of an open internet platform. To us, high speed internet allows for quick access to all types of content.

The second aspect is on content. Today, there is so much content on normal media platforms but these are not available on the internet.

The third aspect is focused on encouraging entrepreneurs t o develop a high-growth industry.

Internet in French-Speaking Africa: What are the differences that exist among the regions in French-speaking Africa?

There are many differences that exist among the countries. I will look beyond the Francophone region and talk about it in a global manner. It is difficult to draw conclusions because there are about 50 countries in Africa with different characteristics and contexts. We group and analyze these countries based on certain aspects.

One criterion that affects the access to internet is the policies and regulation of telecom operators in each country. This environment often determines the state of the market. It is in this case that we see enormous differences in the English-speaking countries in East Africa and those of West Africa especially the Francophone countries. In general, there is a difference between French-speaking and English-speaking countries. We have some policies that I will say are very modern. As the sector evolves though, the policies have to adapt to an environment that changes very fast. This is often not the case in many countries. For example, Senegal changes it’s polices every ten years. There is a telecoms code that came into effect in 2001 and another new code which has not been implemented. So, this market which has changed drastically over the years is governed by a regulatory policy which has been in effect since 2001. The capacity of the regulatory system to adapt to the market is a modernizing factor.

A second important regulatory aspect is the segmentation of licenses. The old polices (of 20 years ago) are based on monolithic licenses. One license was enough to become a mobile Operator.Today, when we look at the telecoms market, there are many operators that carry out different functions. For example, there are those who provide data (ISP), those who develop mobile towers and antennas which are then shared by different operators. Also, there are those who provide infrastructure and those who provide Voice over IP (VoIP) on mobile phones and fixed lines.

A second important regulatory aspect is the segmentation of licenses. The old polices (of 20 years ago) are based on monolithic licenses. One license was enough to become a mobile Operator.Today, when we look at the telecoms market, there are many operators that carry out different functions. For example, there are those who provide data (ISP), those who develop mobile towers and antennas which are then shared by different operators. Also, there are those who provide infrastructure and those who provide Voice over IP (VoIP) on mobile phones and fixed lines.

The last criterion of modernity in licenses is linked to the fact that the telecoms sector was created on the basis of concessions run by a third-party so that the latter could bring revenue for the government. This political approach for a long time focused on revenue-making than on the impact the telecoms sector made on the economy. Modern policies will therefore have to measure the impact that each policy will have on the sector and the economy in general. When we look at these three criteria, French-speaking African countries still rely on archaic methods, which do not allow for the existence of a large number of actors and they target a small number of actors that are taxed heavily (Benin, Mali, Senegal, Cameroun, etc). However, we have the total opposite (with an eye on long term benefits) in English-speaking African countries and in Mozambique (in view).These points create two criteria that distinguish the countries.

Following this, we arrive at a certain market structure. In certain countries, you have a market with a small number of actors who are vertically integrated and who do everything. Take for example, Senegal. There are three mobile operators and one internet provider. In Benin, there are 5 operators. Now take Ghana as another example, there are 5-6 operators and about 20 internet providers and numerous actors who deal with content. In Kenya, there are 13 providers of international capacity and 5 infrastructure providers. Here, the mobile sector is not as competitive, as Safaricom dominates the market (85%) but at least there are many actors who intervene enormously. So, we categorize the countries according to these 3 criteria: 1. Type of controls 2. Market dynamics; and 3. The state of infrastructure

The 4th criterion of the ecosystem is the amount of investors that are present on the market, who create employment and value and those which the African governments have not grasped or encouraged.

On the Francophone Marketplaces, what are the methods of payment? What do you think of these new actors?

For a long time, it was said that the classic e-business solutions could not work in Africa because we were lacking some key elements in the African digital ecosystem like payment portals. Now, when we look at the new actors on the market like Rocket International, Jumia, Kaymu, and Kangoo in Nigeria, there are two phenomena that have aided their growth:

First of all, there is the emergence of the growing middle-class in African mega-cities. These people have a standard of living that is quite similar to what you see in Europe or in the United States. They possess credit cards and buy online due to their style of living. Once, this middle class increased; a market was created, in order to duplicate the same style seen in Europe.

That is one of the reasons Jumia, Kaymu, Jovago, etc arrived on the market. They were even innovative enough to cater for the rest of the online population by providing new payment solutions. In fact, we always thought that mobile phones would constitute a useful tool for payment. But today, when we look at these actors, they have bypassed the mobile and are offering the method of payment on delivery. They do not make use of mobile phones as a method of payment.

This means that the operators have missed a great opportunity. They have all dragged their feet in the provision of an Application Provider Interface (API) to developers. This only has to do with Francophone Africa. Safaricom with its famous tool M-PESA will soon provide an online payment solution. On the other hand, Orange has just announced that it will start testing its Orange Money* API with developers. The same goes for MTN Money. So, I think that the operators have yet to explore this potential growth area of Mobile Money which is a method of online payment. Nevertheless, there are a good amount of users who make use of mobile payments for money transfers and bill payments. It is therefore not surprising that these solutions have arrived with the growing middle-class.

Translated by Onyinyechi Ananaba

Copyright Google Photos – Will Marlow The real internet – Charles Roffey –The context of the digital society. Interview of Tidjane Deme on Google’s strategy for francophone Africa . Interview in September 2015

Key words: Google / Telecoms regulation /digital ecosystem / Marketplaces / Mobile Money

(*) Interview carried out in September 2015 for a professional thesis on the levers in digital marketing for the promotion of African cultural products– ILV Paris – MBAMCI