Throughout the centuries, technological innovations have shaped relations between individuals, as well as interactions between these individuals and their environment. One can think for example of printing, first used by the Chinese (since the 2nd century A.D.) and then sophisticated and generalized by Gutenberg.

Throughout the centuries, technological innovations have shaped relations between individuals, as well as interactions between these individuals and their environment. One can think for example of printing, first used by the Chinese (since the 2nd century A.D.) and then sophisticated and generalized by Gutenberg.

It has been said that printing strongly contributed to the diffusion of the thinking and ideas since the Renaissance, consequently revolutionising the transmission of information and knowledge between individuals. The development of the internet since the early 2000s significantly modified our ways of life and paved the way to new tools and models of communication. Through this New Information and Communication Technologies (NICT), the world became a "global Village"- globalization as they said!

By revolutionising our surroundings, living environments, our thinking schemes, in a nutshell our daily lives, ICT has reshaped from top to bottom the structure of our societies. At the heart of these transformations, technological innovations brings answers to social, economical and environmental issues. This observation is even more emphasized in African countries-the boom of telecommunication has created ideal conditions for local apps and softwares to develop.

The most striking example is the rise of the mobile telephon in Sub-saharan Africa. The mobile is currently the best way of accessing the internet. According to a study published in 2013 by the GSM Association, the number of mobile subscribers in this area of the world has increased by 18% per year between 2007 and 2012. In Africa, most of the mobile phones are sold with an Android system. This is an operating system on which it is very easy to create mobile applications/softwares. It also enables the creation of synergies between different sectors and contributes to social innovation (e-health, e-learning, and etc), economical innovation (mobile banking, urban waste management, and etc).

First restricted to private use, today ICT is acclaimed in the formal and institutional sphere.It is seen as a real tool for development, for socio-economic growth and for populations looking for emerge in the global economy. These technological innovations also impact in different ways to African GDPs. According to a study of the McKinsey Global Institute (MGC) made available to the public in November 2015, the internet contributes 3.3% to the GPD of Senegal ; 2.9% to the GPD of Kenya ; 2.3% to the GPD of Morroco and 1.2% to the GPD of South Africa [2].

So it is not surprising that ICT is directly mentioned in 4 out of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) adopted by the UN in September 2015. As a catalyst for education, gender equality [3], or driving force of the construction of resilient infrastructures for a sustainable industrialization [4] profitable for all, it is largely admitted that ICT play a major role in the emergence of Africa. This article revisit the role that ICT can play in the emergence of Africa as well as the way they will contribute to inclusive growth on the continent.

1. ICT as catalyst of development in Africa

The interest of ICT in Africa lies on their utilities and the services they allow to develop : they're no longer only used as simple communication materials (private or professional), but rather as real tools of socio-economic development. The help of ICT in the continent went from "leisure use" to "therapeutic use" : they bring solutions to the populations regarding their basic needs : education, health, transportation, nutrition, access to energy and drinkable water, and so on. [5] But this wasn't always like this ; for a very long time, " ICT-scepticals" saw the emergence of these new means of communication as the wood for the trees : a lure that distract the attention away from the "real" issues of Africa : famine, malnutrition, illiteracy, epidemics and pandemics, wars, natural disasters and other calamities attached to the representation that some people (and some still have today!) had of the continent. But isn't time the best ally? On this subject, time has ruled in favour of the "ICT-optimisitcs". Indeed, for a decade, an abundance of mobile applications, developed by innovative start-ups has proved that ICT aren't unnecessary, on the contrary they are one of the solutions to resolve "real" issues african countries are facing.

The most well-known are Obami in South Africa (online plateform of free courses and educative videos), Gifted Mom in Cameroon (mothers and infants healthcare), M-Pesa in Kenya (mobile banking), Jumia (e-shopping), W Afate in Togo (3D printer made from electronical waste), M-Louma in Senegal (agricultural stock exchange). Every bold initiative illustrates the key role that ICT play in the fight against poverty, in the access for a good education for all, in the access of healthcare. As Alain François LOUKOU [6] emphasized "ICT aren't a problem completely disconnected from other development-related issues. They rather as in interaction with them." Moreover, the use of ICT through the development of mobile applications has an extent of intergenerational responsibility, not highlighted in the analysis of the rising of ICT in Africa. Indeed, by developing an application as Gifted Mom or Obami, the developers have responded to actual needs as well as those of future generations : access to healthcare and education and so on. In that sense, ICT are well and truly tools that will allow the reach of the SDGs as set by the UN. Thus, we can paraphrase the definition of sustainability saying that ICT are technologies enabling to answer to the needs of the present generations as well as those of the future generations.

2. ICT as tools of inclusive growth

It is undeniable that ICT contribute to boost development for the african continent. The time we saw ICT as luxury for Africa (prey to heavy structural and infrastructural backwardness) is over. Today thanks to ICT, many african entrepreneurs offer to their compatriots local solutions to local problems. But some initiatives even have an international impact, this is "glocalization" : develop local solutions that can extend beyond the national market (especially in countries that share the same issues). For instance, this is the case of the applications for money transfer by mobile in companies where very few private individuals own classic bank account, but do own 2 or 3 mobile phones. Today the thought isn't about the usefulness of ICT for Africa's development. The fundamental question now is: how ICT can contribute efficiently to a sustainable and inclusive growth for african countries?

In front of all the benefits mentioned, rulers and economic agents get down to the job to implement strategies promoting ICT through the rising of digital economy. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, digital economy can be defined as the whole wealth-generating economic and social activities that are activated by plateforms such as the internet, the mobile phones or sensors, including e-commerce. This new category of the economy includes the ICT sector, digital-oriented sectors which couldn't exist without these new technologies. The versatility of the technological innovations makes them vehicles for growth, productivity and competitiveness in some fields such as agriculture, finance, access to energy, consumer goods and services, and so on. Yet, for ICT to become true growth levers, necessary resources have to be mobilised.

a. The role of States

Starting by an offer in education and formation that are in line with the needs of the employment market. Very few educational structures provide courses to learn how to use ICT : very few elementary schools, middle schools, high schools in Africa have computers for computer science teaching. Rare are the schools that offer internet classes or workshops. Learning is completely informal (with friends, family and internet café).

There's no point of specifying the downward slides that this lack of frame engenders (communication tools hijacked for unethical purpose).

A lot of learners are self-taught men and women, or have followed courses in training structures dedicated to ICT [7]. Those trainings come too late in the global educative offer when not marginal. The sector of digital economy is booming, and its need in skills will be huge in the future. With this aim in mind, Africa needs to form future coders, engineers, IT developers and not remain in a lethargic state that will make the continent a desert of skills.

Besides public administration didn't invest the digital sphere : for a while now, we note a digitalization of the government bodies (website, social media account, access numbers via mobile application, and so on). This indicates a mobilization by the rulers who gradually understand the interest of ICT in the daily management of services. The setting up of a dematerialized administration would allow the States to be more efficient and to better serve their citizens.

b. The role of firms

Let's remind that for an inclusive growth of the african countries, the on-site firms have a key role to play. Still today, internet access is expensive for a lot of private individuals. The rates (very wide so every consumer can be satisfied) often stay very high for a continuing consumption. It's not rare for some people to not have access to internet for several days because their bundle is over. They have to recharge their mobile to have internet. The access to this latest is indeed increasing, but still not enough to fill the North-South digital divide and reduce inequalities inside the regions (rural, suburban, urban areas). High rates are the consequences of the weakness of infrastructures and the weak connectivity inside the continent [8]. The decrease of the prices of the internet "subscriptions" is the minimum requirement in order to guarantee continuous internet access to all.

In order to do that, IT firms in collaboration with the states and investors have to work to improve telecommunication infrastructures. As part of their Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), it would be to the firms’ advantage to deploy telecommunication networks more efficient and modern : the dilapidation of equipment and the low rate of electrification on the continent are the biggest handicaps impacting the quality of the services delivered by the operators.

The lack of funds in the telecommunications sector can be resolved by the setting up of guarantees and by an improvement of a business climate more healthy and responsible. Together with the States, firms have to fight against corruption and unfair practices. This is how african countries will know how to appeal new investors, to compensate the low renewal of equipment and the dilapidation of infrastructures. The difficulties stemming from this dilapidation are also the result of the failure in the maintenance of the infrastructure. These lacks can also be explained by the lack of human resources highly qualified. Still in the frame of CSR, firms can benefit from the strengthening of the skills and capacities by building partnerships with training centers, so these latest can train apprentices to the jobs firms really need. Once more, education and training offers are at the heart of the impact of ICT on african countries' development.

Let's mention, before ending this article an element little addressed in the thoughts on ICT in Africa : the management of electrical and electronical waste (EEW). In a context in which the communication between 2 rival operators is excessively expensive, consumers have taken the habit of having multiple phones (one for each operator) or one phone with multiple chips. It is necessary to add to this, tablet computers, laptops and computers. If we consider that each individual changes his mobile phone every 18-24 months, all of this represent a ton of waste badly recycled or even not recycled. Some cautions (for example wearing protection equipments) have to be taken in the treatment of this waste. Indeed all of these devices are composed by elements that are toxic for humans' health and environment if not correctly recycled. Without regulations, the market of recycling and EEW's increasing is mostly informal, so subject to severe negligence in the respect of security measures. In the frame of CSR, telecommunication firms will have to find solutions to manage "e-waste". These latest, if neglected, would generate severe health issues to recyclers (cancer, breathing issues) and severe environmental damages (pollution of ground waters and grounds close to the wild sorting and recycling centers.)

ICT are indeed tools in the service of the sustainability of Africa, but if we think further, we can confirm that with some fulfilled prerequisite, ICT can be catalysis for the sustainable and inclusive growth of the african countries. We've enumerate some improvement targets for the States and the firms as they are the main actors of the development of the continent ; without denying though the importance of civilians on this path toward emergence. ICT are today a key link of the economy of a lot of african countries, and the contribution of the internet might reach 5 to 6% of the african countries' GPD by 2025. This reveals that the sector is highly dynamic. It is necessary to add an informal sector whose datas are "informal" and escape to any formal statistics. The informal sector generate thousands (even millions) of small jobs and substantial incomes to people from every age and sex, who practice wherever networks are available.

To confirm those facts, reliable indicators should be set up in order to appreciate the real impact of ICT on the development of african societies. There are two trails to do this : on one hand, quantify the share of digital economy in the africans GPDs (for example, through the number of descent and lasting jobs created in the ICT sector). We mention countable approaches because they express themselves uniquely in financial terms or job creation. On the other hand, quantifying the shortfalls in case of "deprivation" of ICT ; we would evaluate the organizational consequences of unused ICT on firms, private individuals and administrations."

Translated by : Ornella-Ashley Sangronio

Original Article by: Rafaela ESSAMBA

[1] http://www.gsma.com/publicpolicy/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/gsma_ssa_obs_exec_french_web_01_13.pdf

[2] http://www.medias24.com/MEDIAS-IT/pdf6666-En-Afrique-Internet-est-promis-a-un-bel-avenir.html

[3] 5.b Renforcer l’utilisation des technologies clefs, en particulier l’informatique et les communications, pour promouvoir l’autonomisation des femmes

[4] 9.c Accroître nettement l’accès aux technologies de l’information et de la communication et faire en sorte que tous les habitants des pays les moins avancés aient accès à Internet à un coût abordable d’ici à 2020

[5] Besoins qu’on peut assimiler aux 2 premières bases de la pyramide de Maslow à savoir les besoins physiologiques et ceux de sécurité/protection

[6] Alain François Loukou, « Les TIC au service du développement en Afrique : simple slogan, illusion ou réalité ? »

[7] Signe d’un fort engouement pour l’économie numérique et les TIC, des espaces d’innovation digitale (hub, pépinières, espace de co-travail, incubateurs..) voient de plus en plus le jour en Afrique.

[8] La plupart des pays africains utilisent la largeur de bande passante internationale pour un partage de données au niveau local ; opération extrêmement chère.

[9] http://www.geo.fr/environnement/actualite-durable/le-ghana-poubelle-pour-les-e-dechets-25740

L’Afrique des Idées a rencontré S-Cash Payment, une solution bancaire, totalement digitale. Son fondateur Lionel Yao, revient dans cet entretien sur le rationnel derrière la mise en place de cette plateforme.

L’Afrique des Idées a rencontré S-Cash Payment, une solution bancaire, totalement digitale. Son fondateur Lionel Yao, revient dans cet entretien sur le rationnel derrière la mise en place de cette plateforme.

600 million Africans have no access to electricity while the energy sources, especially renewable energies (RE) abound on the continent. Its key features: environment friendly, availability and its recent cost competitiveness gains over fossil energy; make renewable energy an excellent avenue to start an energy revolution in African. However, having affordable, sustainable and smooth access to energy has a cost. Public policy in investments promotion and risk mitigation in the RE sector are among other issues on which African Government should work on.

600 million Africans have no access to electricity while the energy sources, especially renewable energies (RE) abound on the continent. Its key features: environment friendly, availability and its recent cost competitiveness gains over fossil energy; make renewable energy an excellent avenue to start an energy revolution in African. However, having affordable, sustainable and smooth access to energy has a cost. Public policy in investments promotion and risk mitigation in the RE sector are among other issues on which African Government should work on.

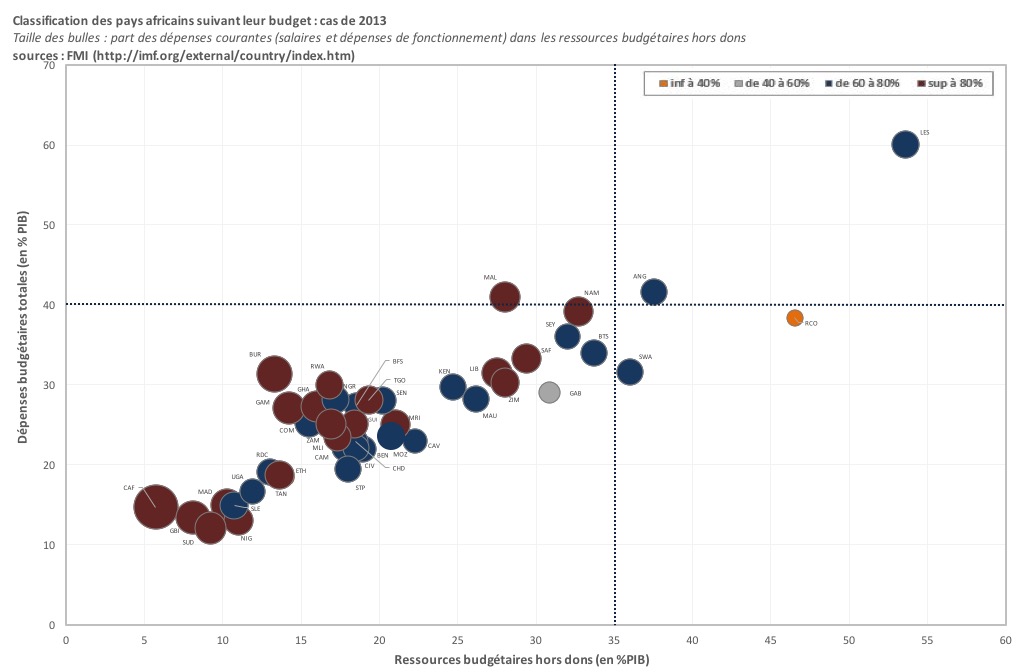

Source: IMF – Classification of the budgets of African countries in 2013

Source: IMF – Classification of the budgets of African countries in 2013

Since the 2000s, a few African countries have committed to strategies, initiated by the World Bank and then extended to the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), to fight against poverty. These strategies, compiled in what are generally called Poverty Reduction Strategic Papers (PRSPs), are based on the dogma which considers that growth is enough to reduce poverty. Therefore, they highlight growth acceleration and identify measures to be implemented to improve the living conditions of the poorest.

Since the 2000s, a few African countries have committed to strategies, initiated by the World Bank and then extended to the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), to fight against poverty. These strategies, compiled in what are generally called Poverty Reduction Strategic Papers (PRSPs), are based on the dogma which considers that growth is enough to reduce poverty. Therefore, they highlight growth acceleration and identify measures to be implemented to improve the living conditions of the poorest.