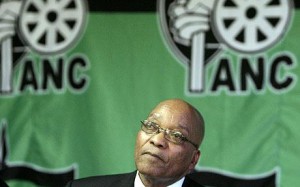

South Africa has lately become restless with a new scandal that is slowly stealing the limelight from the Oscar Pistorius scandal. The cameras have left, at least temporarily, the highly-mediatized trial of the murder-accused athlete to focus on a much more important issue to the South African democracy: the upgrade at an exorbitant cost of President Jacob Zuma's private residence.

South Africa has lately become restless with a new scandal that is slowly stealing the limelight from the Oscar Pistorius scandal. The cameras have left, at least temporarily, the highly-mediatized trial of the murder-accused athlete to focus on a much more important issue to the South African democracy: the upgrade at an exorbitant cost of President Jacob Zuma's private residence.

Zuma owns a private house in Nkandla, a town in his home province of KwaZulu-Natal. One of his wives live in the estate, a kraal designed in accordance with Zulu traditions. When he became President in 2009, he decided to upgrade the Nkandla homestead, alleging the need for security improvements. This was the beginning of a huge scandal that is still making the headlines.

As early as 2009, South Africa's leading daily newspaper, The Mail & Guardian, broke the Nkandla story and disclosed its huge cost and its opaque financing, estimated at the time at 65 million rand (€5 million). Five years later, the expenses have quadrupled. Nklandla has cost at least 246 million rand (€17 million). In contrast, the security upgrades to former President Thabo Mbeki's private residence cost a mere €800,000. Among Nkandla's "security" improvements: a swimming pool, an amphitheatre, a full-sized soccer field, a cattle enclosure and a chicken run.

Since the case was brought to public attention, questions have been raised about the origin of the money used to carry out these upgrades. For a long time, Zuma denied using public funds for his private benefit, claiming that only the security improvements which were required by his presidential status were funded by the state. This version of events, questioned by a series of media investigations, eventually collpased last week after the publication by South Africa's Public Protector Thula Madonsela of a damning report. In this 433 page document, Madonsela provided accurate details on how the President used public funds for works that had absolutely nothing to do with security, and she is now requesting the President to pay back "a reasonable percentage of the expenditure". The architect who supervised the construction happens to be a friend of Jacob Zuma: he was appointed by the President himself, in violation of tendering processes for public works. He reportedly took advantage of this connection to raise his fees and pocket about €2 million himself. Even more critically, the President is accused of misleading inquiries parliamentary inquiries on the subject with repeated false statements.

This is far from Zuma's first encounter with the South African judiciary. In 2007, he faced 783 charges of corruption, fraud, extotion and money laundering, and his financial advisor was sentenced to 15 years of imprisonment. Given the seriousness of the accusations and the media coverage of the "Nkandlagate", he could face trial again. As the Public Protector's report was published, two opposition parties, the Democratic Alliance (DA) and the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) officially lodged a complaint against the President for corruption and misuse of public funds.

However, it is mainly through its political consequences (or non-consequences?) that the Nkandla scandal is raising issues. This new scandal confirms one more time the excesses of the South-African democracy that is considered to be one of the most robust democracies on the African continent. The (con)fusion between the state and the ANC which has characterised South African politics since the end of apartheid has worsened under Zuma. The President has built himself a business empire while governing the country: Zuma and 15 relatives now control more than 130 companies, three-quarters of which were registered in the past few years. Government decisions are increasingly influenced by the private interests of senior party officials or their entourage. With everyone trying to get the largest slice of the pie, the party is increasingly subject to divisions and factionalism. South Africa's political life is now largely determined by the balance of power between the ANC's different tendencies and the outcome of their internecine fighting.

In many other democracies, a scandal such as Nkandla would have been enough to bring the downfall of the President and his government… but obviously, not in South Africa. The party in power is divided; the state is undermined by corruption; two years ago the police cold-bloodedly killed 34 minors while attempting to repress a protest and the investigation is at a standstill; the economy is struggling to recover from the economic downturn, the national currency has experienced one of its worst depreciations… And nevertheless, the ANC system survives and does not seem at risk of collapsing anytime soon. The party's popularity has waned over the past years and support at the polls is eroding. Yet, considering the recurrent scandals and the government's poor performance, the fall is surprisingly slow. According to the latest surveys, the ANC is expected to retain a comfortable majority (about 60 percent) at the May 7th general elections. Zuma is heading for re-election, and if the surveys are to be trusted, the Nkandla affair will have little influence over the election results.

Among the reasons most frequently cited to account for the ANC's resilience is the weakness of opposition parties. The Democratic Alliance may have doubled its share of the vote in the past decade, but it is still struggling to expand beyond its traditional Western Cape stronghold and to reach out to the non-white, non-coloured electorate. It will probably not reach more than 30 percent of votes in May. The Congress of the People (COPE), which had brought together in the 2009 elections dissident members of the ANC disappointed by Thabo Mbeki's ousting, has now collapsed. The new leftist party, the Economic Freedom Fighters is having a hard time rallying support, despite the charismatic personality of its president and founder, Julius Malema, the former president of the ANC Youth League: surveys predict that the EFF should not exceed 4 percent of the votes.

The argument is obviously hard to disprove: voters need to be convinced by attractive alternative solutions to turn away from the ANC, and these alternatives are currently lacking credibility. However, there are two other deeper causes that explain why the party manages to maintain such a powerful position.

– On the one hand, the widening gap within South African society between urban areas – where a more "cosmopolitan' electorate increasingly rejects the ANC's governance practices -, and rural areas, where the ANC has maintained an near-total control.

– On the other hand, a peculiar historical context, which has deeply influenced the demands of South African citizens for government accountability.

Since the end of apartheid, South African society has changed radically, and studying social relations only through a racial lens is certainly not sufficient. it would be clearly simplistic to study social relations only through the racial lens. Since the mid-1990s, South Africa has rapidly embraced globalisation; yet, this integration was partial and mostly limited to the cities, who benefited from an influx of investors, tourists and migrants from all over the world. Cities like Johanesburg, Cape Town or Durban have become global metropolitan centres, well-connected and integrated to the world-system. Their residents, immersed in political and economic liberalism, are often very critical of the ANC's clientelist practices. Meanwhile, South Africa's rural areas have been largely excluded from globalization. The ANC, which was paradoxically an urban movement until the end of apartheid, has reached out to the countryside, where it now exerts a near-total control. In these isolated areas suffering from high unemployment, ANC officials have managed more easily to position themselves as local patrons and to develop clientelist systems, guaranteeing proper rewards for their loyal supporters and making sure that no other party would threaten their local control. These rural regions today guarantee the ANC's continued electoral success.

Moreover, the attitude of South African citizens and taxpayers towards government and public management is still influenced by the country's historical legacy. In a society where inequalities are extreme, and still strongly related to racial issues, the population does not reprehend the accumulation of wealth by a black elite. Such practices are not seen as corruption or misuse of funds but rather as examples of self-achievement and individual success. Individuals such as Malema and Zuma, by becoming nouveaux riches, are viewed as attacking the issue of existing inequalities,throwing the first stone against the citadel of white economic domination, and that inspires respect. It does not fundamentally matter that their wealth may have been built by the misuse of public funds; and that is why some South Africans still believe that the Nkandla scandal should be regarded as a private issue, unrelated to the management of public affairs.

Rural areas have not been much exposed yet to Western principles of electoral democracy. They are not entirely familiar with the key notion of "sanction-vote". In mature democratic systems, people in power have to account for their actions. Voters evaluate government performance during its last mandate and decide whether they will trust the members of the government again or sanction them. This demand for results is a short-term requirement, which accounts for regular changes in power.

In South Africa's young democracy, the memory of the apartheid is still vivid and the requirement for results does not the same frequency. Voters evaluate results on the long term, and not only with regard to the last presidential mandate. The past mandate of the ANC in power was undoubtedly tainted by a range of problems and excesses. However, in the past two decades, its results are undeniable: the situation has certainly improved for rural populations since the end of the apartheid. And many voters still consider that a good enough reason to continue voting for the ANC and Jacob Zuma, regardless of Nkandla, its swimming pool and its football pitch…

Translated by Bushra Kadir

Près de vingt ans après son arrivée démocratique au pouvoir et la planification de ses objectifs à travers le Reconstruction & Development Programme (RDP), le gouvernement de l’ANC tire un bilan de son action et fixe les grandes lignes de sa volonté politique et économique d’ici à 2030, pour la prochaine génération de Sud-Africains.

Près de vingt ans après son arrivée démocratique au pouvoir et la planification de ses objectifs à travers le Reconstruction & Development Programme (RDP), le gouvernement de l’ANC tire un bilan de son action et fixe les grandes lignes de sa volonté politique et économique d’ici à 2030, pour la prochaine génération de Sud-Africains.

L’arrivée au pouvoir en 2009 du président Jacob Zuma a coïncidé avec la volonté pour l’ANC de porter un regard critique sur son propre bilan afin de construire, sur cette base, les lignes de son projet d’avenir pour l’Afrique du Sud. Une démarche rigoureuse et honnête qui mérite d’être saluée. Cette tâche difficile a été confiée à Trévor Manuel, ancien ministre des Finances sous les deux mandats de Thabo Mbeki. En juin 2011, un premier Rapport de Diagnostic sur le bilan de l’ANC est rendu public. Ce diagnostic est sans concession, qui reconnaît d’emblée que « les conditions socio-économiques qui ont caractérisé le système de l’apartheid et du colonialisme définissent encore largement notre réalité sociale ». Tout en se félicitant des réelles avancées connues depuis 1994 – l’adoption d’une nouvelle Constitution pour l’égalité des droits et l’établissement de la démocratie ; le rétablissement de l’équilibre des finances publiques ; la fin des persécutions politiques de l’apartheid ; l’accès aux services publiques de première nécessité (éducation, santé, eau, électricité) pour des populations qui en étaient privées – le rapport de diagnostic reconnait que la situation présente de l’Afrique du Sud pose problème. La pauvreté reste endémique et les inégalités socio-économiques ont continué à se creuser, faisant de la Nation arc-en-ciel le deuxième pays le plus inégalitaire au monde après le Lesotho[1].

L’arrivée au pouvoir en 2009 du président Jacob Zuma a coïncidé avec la volonté pour l’ANC de porter un regard critique sur son propre bilan afin de construire, sur cette base, les lignes de son projet d’avenir pour l’Afrique du Sud. Une démarche rigoureuse et honnête qui mérite d’être saluée. Cette tâche difficile a été confiée à Trévor Manuel, ancien ministre des Finances sous les deux mandats de Thabo Mbeki. En juin 2011, un premier Rapport de Diagnostic sur le bilan de l’ANC est rendu public. Ce diagnostic est sans concession, qui reconnaît d’emblée que « les conditions socio-économiques qui ont caractérisé le système de l’apartheid et du colonialisme définissent encore largement notre réalité sociale ». Tout en se félicitant des réelles avancées connues depuis 1994 – l’adoption d’une nouvelle Constitution pour l’égalité des droits et l’établissement de la démocratie ; le rétablissement de l’équilibre des finances publiques ; la fin des persécutions politiques de l’apartheid ; l’accès aux services publiques de première nécessité (éducation, santé, eau, électricité) pour des populations qui en étaient privées – le rapport de diagnostic reconnait que la situation présente de l’Afrique du Sud pose problème. La pauvreté reste endémique et les inégalités socio-économiques ont continué à se creuser, faisant de la Nation arc-en-ciel le deuxième pays le plus inégalitaire au monde après le Lesotho[1].