The African Union Summit held in July 2014 in Malabo has endorsed the establishment of an African court of justice and human rights. This Court was created in June 1998 following the Protocol on the African Charter of Human and Peoples' rights in Ouagadougou, which entered into force in 2004. Nevertheless, it takes place in a context of strong opposition between African political leaders, the African Union and the ICC. This « African criminal court » is seen as an answer to the ICC bias in Africa. However it suffers from the same shortcomings and will stay, just like this institution, under the influence of the political interests of the states.

The African Union Summit held in July 2014 in Malabo has endorsed the establishment of an African court of justice and human rights. This Court was created in June 1998 following the Protocol on the African Charter of Human and Peoples' rights in Ouagadougou, which entered into force in 2004. Nevertheless, it takes place in a context of strong opposition between African political leaders, the African Union and the ICC. This « African criminal court » is seen as an answer to the ICC bias in Africa. However it suffers from the same shortcomings and will stay, just like this institution, under the influence of the political interests of the states.

Many people think that the ICC cares only about Africans. Since its implementation in 2002, the ICC has indicted about 30 people who were all African. As a matter of fact, the institution has often been accused of being an instrument of neo-colonialization used against Africa and its political leaders. This idea could have been considered as marginal and related to political partisanship. But, the African Union and many political leaders seem to go down this path in the past few months.

The indictment of Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta and his Vice-president William Ruto for crimes against humanity because of their financial support to 2007-2008 post electoral violence, seems to have reignited the latent tensions between the African Union and the ICC.

Actually, in 2009 after the indictment of the Sudanese President, Omar el Bechir, the pan-African organization had already declared that it would not collaborate with the ICC.

The Addis-Ababa Summit of October 2013 was yet another step towards the separation of these two institutions, since an eventual collective withdrawal of African States was on the agenda. And even if it did not happen, the implementation of the new Court of Justice, created to prosecute war crimes, crimes against humanity and crimes of aggression, is pulling the rug out from the ICC.

It is true that the weight of western countries on the organization funding (with 60% of the budget coming from the European Union) and on nomination of judges can give them a great influence on its activities. It is the opinion of Mahomood Mamdani, an Ugandan professor who considers that western countries have way too much influence on the ICC and that, in the light of historical relations between Europe and Africa, the place occupied by the black continent in this court gives an impression of « deja vu ».

However, this negative view cannot resist an advanced analysis. It is true that the ICC has several downfalls. The UN Security Council can ask the institution to address activities such as « war or aggression crimes and crime against humanity » although 3 out of 5 permanent members have not signed or ratified its founding treaty: the Rome Statute.

Thus, the United States, China and Russia influence or hinder, according to their political interests, the ICC's work, without acknowledging it legally. The recent struggles about the involvement of the ICC in the Syrian conflict within this Council shows the political importance of the institution as it is a passive instrument of these States.

In the African context, it is often forgetten that the ICC only took the Kenya case at its own initiative. The former prosecutor, Luis Moreno Ocampo, decided to investigate the implication of Uhuru Kenyatta and William Ruto in the post electoral violence on his own initiative. It is true that Kenyatta and Ruto are not the only politicians in the world who are suspected of mass incitment to violence. For the vast majority of other trials against African citizens, individuals have been referred to the Hague Court by states themselves, because local jurisdictions are incompetent to prosecute these crimes. Laurent Gbagbo has been charged by the ICC because the Ivorian government had transfered his case to the Court. The same goes for all the Congolese rebel leaders tried by this court. This would not have been possible without the collaboration of African states and leaders who vilify the ICC.

Besides, the ongoing charges against Kenyatta and Ruto is problematic since they are two of the highest state authorities in Kenya. Where does national sovereignty end and where does the right to justice start?

Just like the case of Laurent Gbagbo, the trials of these two statesmen are highly politicised and divide the citizens of their own countries. These three personalities are very different from what the ICC is used to handle. The first ones to be tried by the Court rarely had the same political capital to defend themselves against an international Court. The Court was more focused on principles than on the monopoly of violence because it depended too much on the states' will and their strategic interests to be able to genuinely deliver an impartial justice.

The recent creation of an African Court for justice and human rights seems to respond to this context of tensions between African state leaders and the ICC. This criminal court will become operational in a couple of years. The simple fact that it was voted almost unanimously (apart from Botswana) is a strong signal in favor of the ICC.

The ICC is, by virtue of the subsidiarity principle, the highest court for crimes for which national jurisdictions are incompetent. Thus, the African Union pulls the rug out from the ICC, but the commitment of African states towards a transparent and truthful continental justice can already be questioned.

A clause of this new Protocol gives immunity to Heads of states during their mandate and “High officials" in duty. Uhuru Kenyatta, William Ruto and Omar el Bechir shall not be prosecuted by this court, despite the serious allegations of crime against humanity they are facing. Moreover, given the Heads of States' tendency to hand over power only when they are forced to do so, it is feared that this clause will encourage them to stay in power longer.

This clause and this court could become obstacles to the democratic consolidation that started in Africa since the early nineties. Plus, African States did not stand out by their enthusiasm for an African international justice. The protocol on the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights was signed in 1998, but was ratified by only 15 out of 53 members of the African Union.

All this controversy brings us back to the debate on the possibility of a genuine international justice. Torn between legal considerations and morality, it finally depends on the political willingness of states and their power to implement it. The African Court of justice and human rights will face the same issues and criticisms as the ICC, to which it seems to be a substitute for Africa.

The political weight of states and leaders will always determine their position with this court. Ultimately, African states will repeat the same attitude that they reproached to the ICC. After all, partiality is inherent to any mechanism based on political considerations and national interests.

Ousmane Aly Diallo

(Translated by: Olivia Gandzion)

Picture 2 : Mandelbrot Set

Picture 2 : Mandelbrot Set

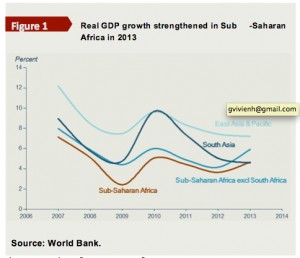

Gone are the days when Sub-Saharan Africa was playing a minor role in the economic world. It’s been a decade now since Sub-Saharan Africa has been experiencing a positive growth and increasing its influence in the world economy. The World Bank confirmed this trend in its last Global Economic Prospects for Sub-Saharan Africa. In this particular report, the World Bank focused on the outlook of this region and found it extremely vulnerable to some downside risks. The purpose of this article is to discuss the factors that cause those risks and suggest some solutions that can help this region steady its growth and surpass East & Pacific Asia who are the best in terms of economic development.

Gone are the days when Sub-Saharan Africa was playing a minor role in the economic world. It’s been a decade now since Sub-Saharan Africa has been experiencing a positive growth and increasing its influence in the world economy. The World Bank confirmed this trend in its last Global Economic Prospects for Sub-Saharan Africa. In this particular report, the World Bank focused on the outlook of this region and found it extremely vulnerable to some downside risks. The purpose of this article is to discuss the factors that cause those risks and suggest some solutions that can help this region steady its growth and surpass East & Pacific Asia who are the best in terms of economic development.

In my first short

In my first short  Inspired in the literature on policy diffusion, we might perhaps want to perceive innovation here as something that ‘it is new to the states adopting it, no matter how old the program may be or how many other states have adopted it’.

Inspired in the literature on policy diffusion, we might perhaps want to perceive innovation here as something that ‘it is new to the states adopting it, no matter how old the program may be or how many other states have adopted it’. pressure to be more cost-efficient notably through the development of innovative production processes; on the other, to stand out of the crowd of competitors, differentiating their products from the existing ones and offering consumers innovative and better products. Innovative companies are those that leave their comfort zone and strive for better products and processes. However, leaving your comfort zone implies taking risks that developing countries might not be willing to embrace. Although ‘necessity is the mother of invention’, innovators in African countries might need a helping hand from their governments to solve the ‘innovation chasm’ that often characterizes them.

pressure to be more cost-efficient notably through the development of innovative production processes; on the other, to stand out of the crowd of competitors, differentiating their products from the existing ones and offering consumers innovative and better products. Innovative companies are those that leave their comfort zone and strive for better products and processes. However, leaving your comfort zone implies taking risks that developing countries might not be willing to embrace. Although ‘necessity is the mother of invention’, innovators in African countries might need a helping hand from their governments to solve the ‘innovation chasm’ that often characterizes them.

Genocide is not a crime as any other. While the other forms of conflicts meet political and economic interests, genocide is a concerted plan in view of eliminating the members of a given group. Genocide aims to “purify” the social group by removing the elements regarded as unworthy to be part of it: Jews in Germany, Blacks in South Africa

Genocide is not a crime as any other. While the other forms of conflicts meet political and economic interests, genocide is a concerted plan in view of eliminating the members of a given group. Genocide aims to “purify” the social group by removing the elements regarded as unworthy to be part of it: Jews in Germany, Blacks in South Africa Goodluck Jonathan is at the moment in a tight spot. The past few months, the Nigerian president has been subjected to a fierce opposition amidst his very own party, The People's Democratic Party (PDP) which has been reigning since the establishment of the Fourth Republic in 1999. Leading a gigantic country in terms of economy and demography (Nigeria is the most populous country of Africa with 170 million inhabitants), President Jonathan has been in power since the death of his predecessor Umaru Yar’Adua in 2010 and is becoming more and more unpopular. In addition to a questionable management of the clashes with the Boko Haram sect, he is suffering from a considerable lack of legitimacy in his party.

Goodluck Jonathan is at the moment in a tight spot. The past few months, the Nigerian president has been subjected to a fierce opposition amidst his very own party, The People's Democratic Party (PDP) which has been reigning since the establishment of the Fourth Republic in 1999. Leading a gigantic country in terms of economy and demography (Nigeria is the most populous country of Africa with 170 million inhabitants), President Jonathan has been in power since the death of his predecessor Umaru Yar’Adua in 2010 and is becoming more and more unpopular. In addition to a questionable management of the clashes with the Boko Haram sect, he is suffering from a considerable lack of legitimacy in his party.